A global partnership to combat antimicrobial resistance

Bacteria worldwide continue to develop resistance to life-saving drugs. Researchers from 6 colleges at North Carolina State University join forces with an international consortium in a fight against antimicrobial resistance.

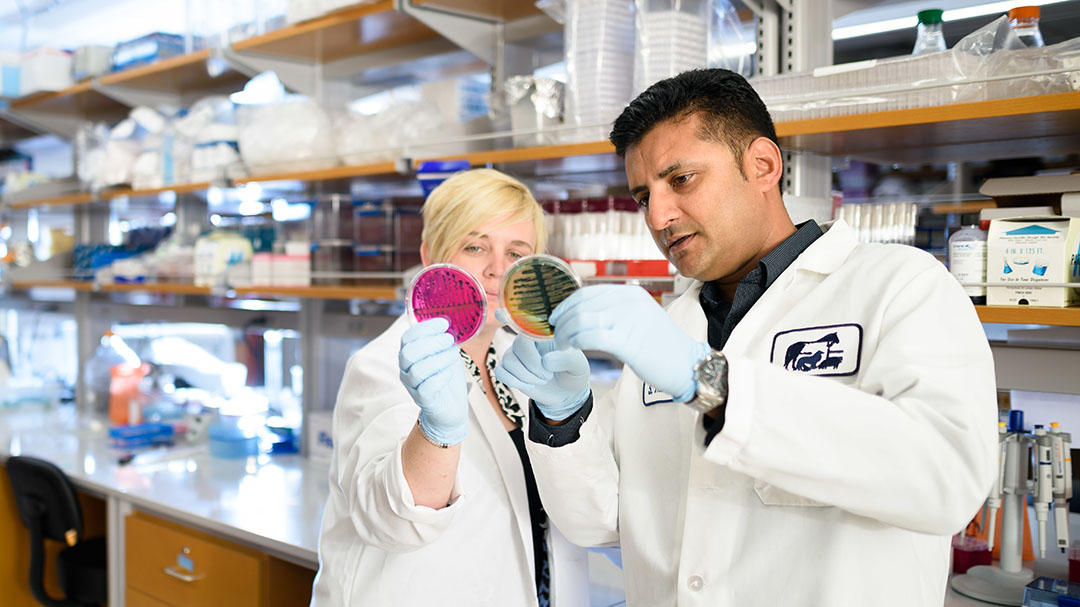

The global partnership is led by Sid Thakur, director of global health and professor of epidemiology at the College of Veterinary Medicine and North Carolina State University (NCSU), and aims to develop new research projects and training programmes worldwide, said Greer Arthur, global health programme specialist at NCSU.

The consortium, said Ms Greer, includes 19 faculty from NCSU, as well as faculty from the University of São Paulo in Brazil, the University of Surrey in the UK and the University of Wollongong in Australia. The scientists represent a range of academic fields, from sociology and economics to human and veterinary medicine and engineering.

“Antimicrobial resistance is constantly advancing and changing,” said Mr Thakur. “We have an obligation to make sure we prepare future generations for the challenges to come.”

Curable infections to incurable diseases

The creation of the consortium follows the latest development in the global antimicrobial resistance crisis: that resistance to colistin, a last resort drug for treating multidrug-resistant Salmonella, has finally arrived in the US. First reported in China 3 years ago, the gene responsible for colistin resistance, mcr-3.1, has since been discovered in countries as far-stretched as Australia and Canada.

“Antimicrobial resistance threatens to undermine decades of antibiotic progress and turn curable infections into incurable diseases,” said Johnjoe McFadden, professor of molecular genetics at the University of Surrey.

“Antimicrobial resistance is a complex threat – it affects human health, animal health, food safety and water quality, just to name a few,” said Maria Tereza Pepe Razzolini, an associate professor of microbiology at the University of São Paulo.

“One key goal is to curb the overuse of antibiotics in various sectors, since overuse is a key driver of antimicrobial resistance,” said Antoine van Oijen, professor of biophysics at the University of Wollongong. “Changing the way we use antibiotics as a society requires the input of a number of different disciplines.”

International research and educational collaboration

Ms Arthur says that each university belongs to the University Global Partnership Network, an organisation established in 2011 that supports international research and educational collaborations addressing some of today’s greatest global problems.

Funded by the UGPN, this November Mr Thakur and his collaborators will convene in Brazil to develop new strategies for studying and combating antimicrobial resistance across continents.

“This consortium will provide space for sharing data and insights, and help influence intervention strategies,” said Ms Razzolini. “We will also be able to perform research and hopefully inform policy at a global level, not just specific to a single country,” added Mr van Oijen.

As well as research, the consortium plans to develop international training programmes to provide students and researchers with the multidisciplinary skills and experience they need to combat antimicrobial resistance on a global scale.

Ms Arthur noted that antimicrobial resistance is one of the major research strengths of the College of Veterinary Medicine’s global health programme. Mr Thakur’s laboratory currently represents North Carolina in 2 national surveillance programmes, namely the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System and the Food and Drug Administration’s Genome Trakr programme.

“This consortium is the next logical step,” said Mr Thakur. “Antimicrobial resistance is a global threat and can only be tackled through international collaboration.”