Big vs. small chickens – the answer is in the microbiome

If you’re involved in the production of poultry, then you’re likely well aware of the relationship between variability and profitability. As a rule, the more uniform your flocks, the more likely they are to be profitable. The microbiome plays a huge role here.

While there are many commonly recognised sources of variation in the uniformity of flocks, including genetics, the age of breeder hens, environmental and physical conditions, and management practices, sometimes the tremendous impact of the microbiome is overlooked.

While there are many commonly recognised sources of variation in the uniformity of flocks, including genetics, the age of breeder hens, environmental and physical conditions, and management practices, sometimes the tremendous impact of the microbiome is overlooked.

The microbiome is the collection of functional genes in the trillions of microorganisms that live in the digestive tracts of the birds in your care. The robustness and general quality of the microbiome can be assessed by examining the relative abundance and distribution of probiotic, symbiotic, commensal, and potentially pathogenic microorganisms.

An experiment

To provide evidence for this concept and to verify the magnitude of the impact of the microbiome, a simple experiment was conducted. A total of 218 male broiler chicks of the same breed, sourced from breeder hens of a similar age, incubated in one incubator and hatched in one hatcher, were placed together in a single 13.2 m2 pen with extra feeders. This was in order to reduce variation as much as practically possible.

At 37 days of age, each of the remaining 211 birds was individually weighed and the caecal tonsils were collected from the 25 heaviest and the 25 lightest birds. DNA was extracted from the contents of those caeca and, using standard sequencing techniques, the microbiome of each bird was assessed.

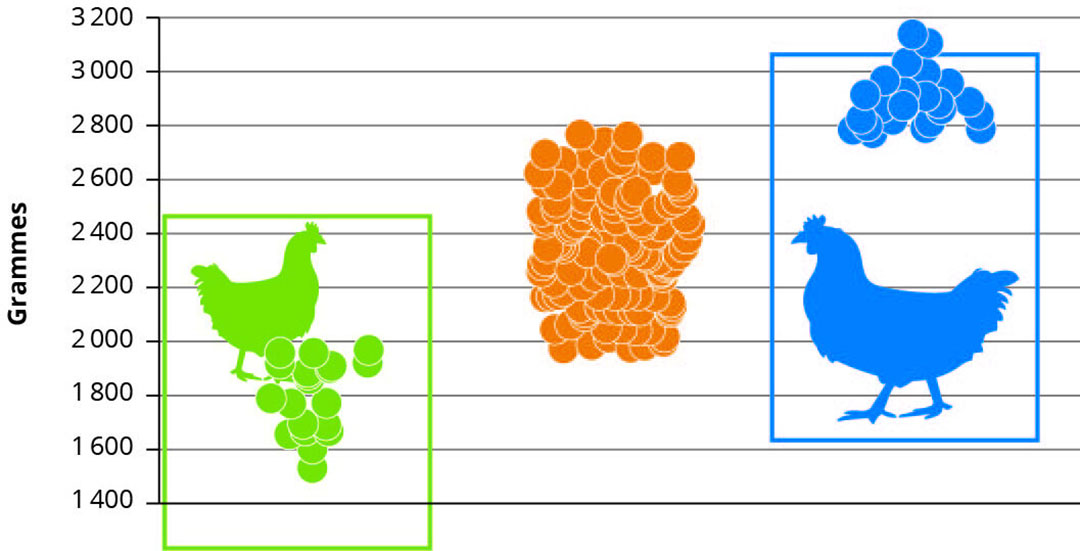

With as much variation as possible controlled, there was still a range of 1,590 grammes from the lightest to the heaviest bird. The 25 smallest birds averaged 1,808 grammes with a coefficient of variation of 6.75%, while the 25 biggest birds were over 1,000 grammes heavier and averaged 2,891 grammes with a coefficient of variation of only 3.46%.

Eubiosis and dysbiosis

We then turned to a set of analyses of their microbiomes to reveal additional sources of variation. The individual microbiomes of the big birds had a significantly greater abundance and a better proportionality of microorganisms compared to those of the small birds. Higher diversity and a better evenness in the distribution of micro-organisms are associated with ‘eubiosis’ – a normal healthy state of the digestive system. In contrast, a lower diversity and uneven distribution of microorganisms was observed among the microbiomes of the small birds, which is associated with ‘dysbiosis’ – an abnormal, unhealthy state of the digestive system.

When considered together, the collective microbiomes of the big birds were significantly more uniform than those of the small birds (Figure 1). Lower variation among the microbiomes of a group is associated with better performance.

Figure 1 – Body weight at 37 days.

An abundance of microorganisms

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, the microbiomes of the big birds had a greater abundance of 31 different micro-organisms compared to the small birds, and each of those organisms is known to be a producer of short-chain fatty acids, such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate. There is a large and growing body of scientific literature that supports the theory that the production of short-chain fatty acids by gut micro-organisms helps people, animals, and birds maintain a state of eubiosis and general emotional and physical health.

Establishing a robust microbiome

Bacteria have been on earth for over 3.2 billion years and all higher forms of life evolved in their presence. It should not surprise us that ‘they’ have a way of communicating with their hosts and can positively influence the host’s health and well-being.

Considering all of the evidence, we conclude that establishing a robust microbiome early in life is the key to success for your birds and your flocks. Failure to do so is a driver of unwanted heterogeneity and potential economic losses.