Density: an underestimated cause of tail-biting

Tail-biting occurs when pigs do not have enough resources to adapt to its environment. In this article, we examine how density remains a major risk, and what pig producers can do about it.

Genetics improvement over the years has increased the prolificacy of the sow. As shown in a study conducted in Spain, the number of piglets born alive increased by 1.9 between 2007 and 2016. But, farming barns haven’t always adapted to this production increase. As a result, punctual or chronic over-density can be observed, especially in fattening stage which drastically increases the risk of tail-biting. Knowing that, density remains a major risk factor in tail biting prevention.

Space allowance: which surface area to respect?

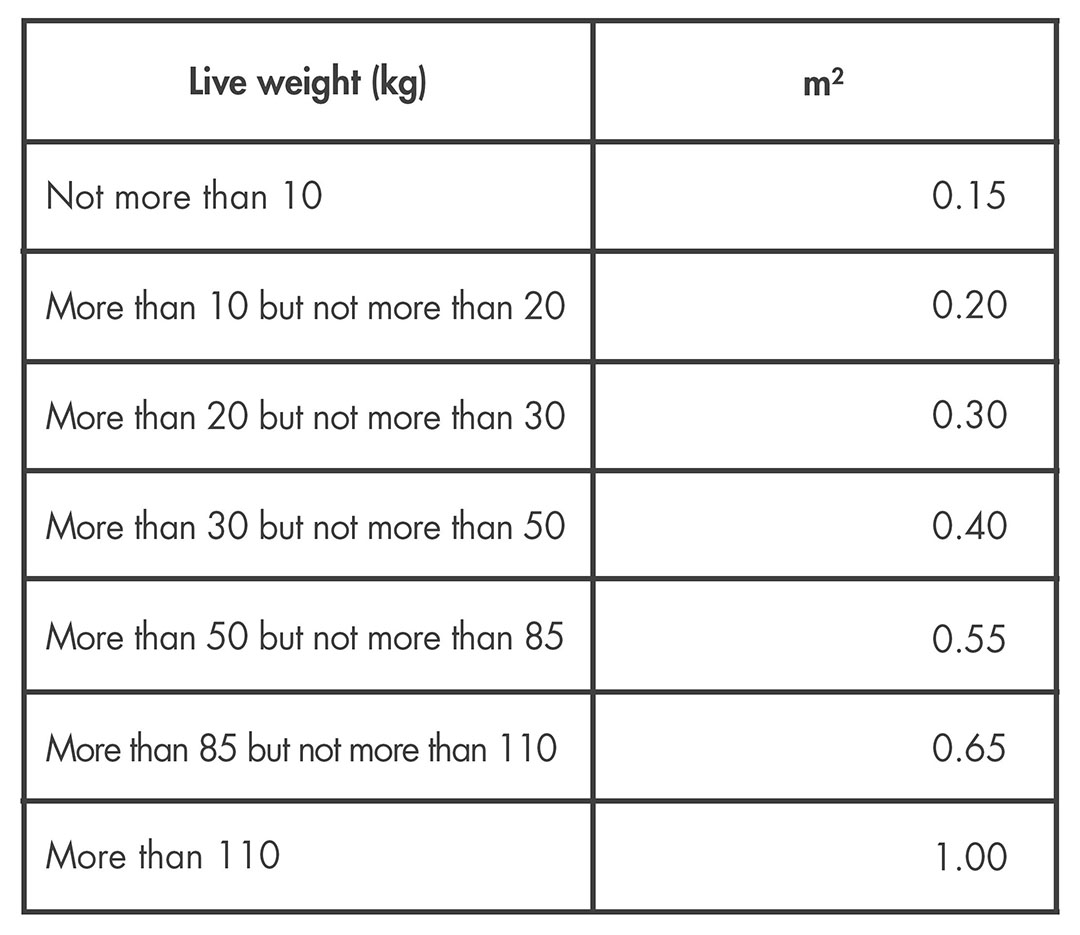

At a European level, space allowance is stated by the Council Directive 2008/120/EC which exposes the density according to body live weight of the animal. Thus, in fattening stage, space allowance is fixed at 0.65 sqm per pig (Table 1).

Table 1 – Minimum space allowance in European in pig (Official Journal of the European Union)

Within quality sectors acting for better welfare, such as Beter Leven in Germany, space allowance is one of the main criteria for awarding the label. More space means better welfare.

Is the standard sufficient to ensure animal welfare?

As space allowance is defined per animal, a pig weighing 50 kg at the entrance of the fattening stage has 0.65sqm until its departure to the slaughterhouse when its bodyweight will be around 110 – 115 kg. Thus, if the surface is than the standard at the beginning of the fattening stage, it becomes limited along the way, with a possible drop in individual performance.

In 2017, Thomas et al. studied the effect of stocking density on pig performance with constant group size throughout the whole experiment (9 animals/pen). Using a predicted equation, in this experiment, average daily feed intake (ADFI) should start to decrease when pigs have reached 83.3kg, with 0.65sqm per pig. This means that beyond this gap, animal performance may be affected. What about the animals’ wellbeing? Does the density stress start at a body weight of 83kg?

When do pigs start to bite?

Tail-biting or cannibalism is a behavioral pathology which occurs when the animal doesn’t have enough resources to adapt to its environment. In other words, once stress is too high, the animal reaches a threshold where it can no longer adapt itself. So, the key question is: when does a pig reach this limit? There are as many possible responses as there are pigs! Indeed, stress is an individual variable: each animal has its own sensibility to stress and its own history which affects its capacity to handle stressful situations.

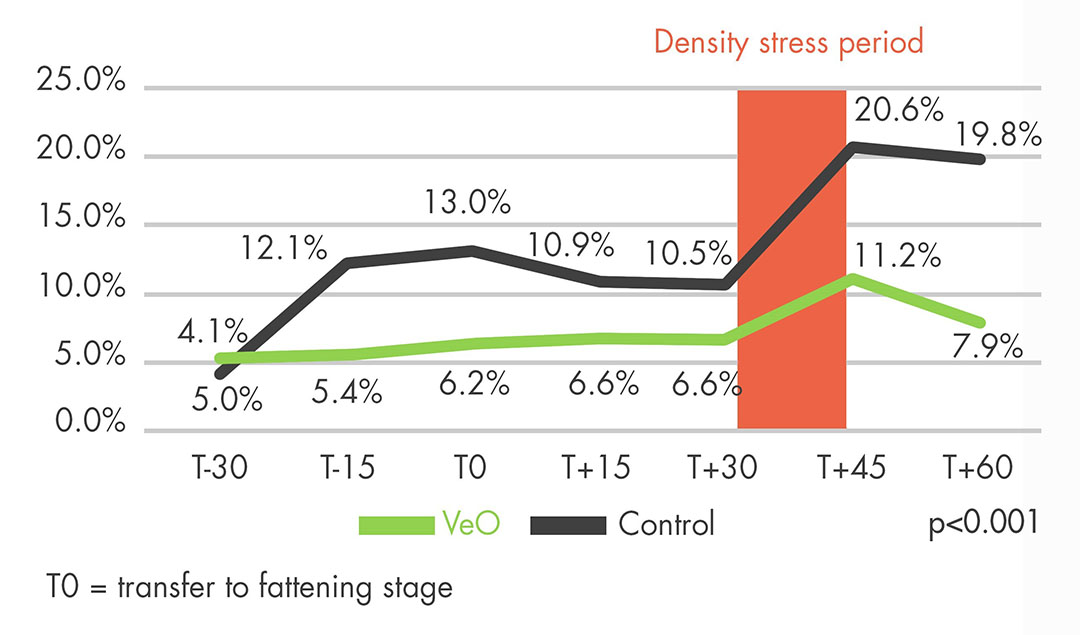

In a study conducted in a breeding farm, tail lesions were measured on gilts from post-weaning (day 50) until the labelling day (day 150) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – The evolution of lesions in a breeding farm

In control batches (247 gilts), an increase of tail lesions was observed 45 days after the entrance of the gilts into the fattening stage, from 10.5% to 20.6%. At this stage, the animals’ average age was 128 days with an average body weight of 88 kg. This peak of tail-biting appears to be the result of density stress.

Limiting density stress

Two options are possible to limit stress due to density: increase the space allowance per pig or lift the threshold of stress. The first possibility has already proven itself. The second solution is to modulate stress response by taking care of the first limiting parameter: the serotonin level. In a study conducted at CNRS, a decrease of serotoninergic neurons’ activity in stressed animals was shown. The serotoninergic neurons’ activity is directly linked to the capacity of the animal to adapt to a stressful situation. This activity can be maintained by the specific solution developed by Phodé, namely VeO Swine.

This product has been tested on the same breeding farm mentioned above, on 26 gilts. Results showed the same evolution pattern in the control and trial batches. However, prevalence of tail lesions was significantly decreased (65%) with VeO (4.7% vs. 13.4% in control groups; P<0.001) over the whole period. Peak tail-biting behaviour was observed at 45 days after the entrance in fattening stage was only 11.2% with VeO (compared to 20.6% in the control groups). The animals fed VeO expressed less cannibalism behaviour yet were kept at the same density level, meaning they adapted better than the control group to the same density stress.

Density is a stressful situation for pigs and decreasing it is not always possible. Stressors are present throughout the whole production cycle. It is therefore beneficial to include VeO in the feed (solid or liquid) to help the animals better handle stressful situations – like density, transportation, regrouping, etc. – to decrease the deviant behaviours like cannibalism, which impair the animals’ welfare and the farmer’s income.