Morrocco rated phosphate kingdom of the world

Morocco is home to the world’s biggest known deposits of phosphate, used in fertilizer, detergent, food additives, and more recently lithium-ion batteries.

Sold for decades in its raw state for less than $50 per metric ton, it’s currently at about $125, according to World Bank figures.

This is good news for Morocco’s King Mohammed VI (47), who owns more than half the world’s phosphate reserves.

The King is the unofficial overseer of the state-owned phosphate monopoly, Office Chérifien des Phosphates (OCP), Morocco’s largest industrial company.

Most traders expect OCP to drive the commodity’s price higher, which means the cost of making everything from corn syrup to iPads will be going up.

Reserves in decline

Phosphate as fertilizer is the engine powering modern agriculture, and its reserves are in decline almost everywhere except Morocco.

Most phosphate mines, including those in the US, which produces 17 percent of global supply, have been in decline for the past decade, running out of quality rock and hindered by environmental regulation. That has forced companies to look farther afield for supplies.

Mosaic, BHP, Potash

Earlier this year, Mosaic Co. spent $385 million for a 35% stake in a Peruvian mine to supply rock to its phosphate operations in the US and South America.

Australia’s BHP Billiton Ltd., the world’s biggest mining company, made a $40 billion hostile takeover offer for Canada’s Potash Corp., a major supplier of both potash and phosphate.

85% of world’s total

The scale of Morocco’s phosphate wealth was officially verified in September, when the International Fertilizer Development Centre released its long-awaited update on global phosphate resources.

Morocco’s portion went from the 5.7 billion tonnes still cited in the 2000 U.S. Geologic Survey reports of, to 50 billion tonnes – 85% of the world’s total.

Even with 170 million tonnes of concentrated phosphate changing hands each year, the Moroccans likely have at least 300 to 400 years of rock available.

Demand rises

With a growing world population consuming more grain, more meat, and more biofuels, demand is expected to rise at a rate of 2 to 3% per year, according to the International Fertilizer Association.

OCP controls 30% of global phosphate exports, and plans to increase annual production from 30 million tonnes to 54 million tonnes by 2015, investing $5 billion in the process.

At September’s World Fertilizer Conference in San Francisco, Morocco’s ascendancy was the main topic of conversation.

Disputed territory

Western Sahara is a disputed territory. It’s also where Morocco’s best phosphate lies. The region known to the King as “Moroccan Sahara” begins just south of the fishing village of Tarfaya on the Atlantic coast.

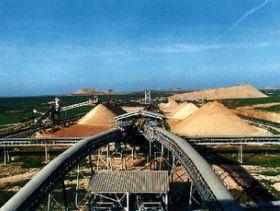

The UN calls it “the non-self- governing territory of Western Sahara” and deems it “occupied.” It’s a place where phosphate rumbles to the coast on the world’s longest conveyor belt, while tanks and soldiers roam alongside, defending the shipments from Sahrawi separatists.

Companies in Australia and Norway have said they no longer use phosphate mined in Western Sahara. In August, Mosaic told the advocacy group Western Sahara Resource Watch that it has stopped buying rock from the territory.

The US, in addition to needing the phosphate, sees Morocco as an ally in the war against terrorism. Last year, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton reaffirmed US support for Morocco’s plan of “limited autonomy” for the territory, which stops short of the independence demanded by the Polisario.

Source: Bloomberg