Poultry experts explore 3 alternatives to culling

Every year, an estimated 7 billion male layer chicks are culled because they have no place in egg production. Societal opposition to the practice has led the industry to look for alternative solutions, and policymakers to discuss banning the now-controversial practice altogether.

Regulations have already changed in several countries. In January 2022, Germany and France became the first 2 countries in the world to ban chick culling. Since then, they have called on other EU Member States to follow suit. Their adopted solutions, however, are unique and the motives behind them, in some cases, questionable. Peter van Horne, poultry economist at Wageningen University & Research in the Netherlands, and Eddy Decuypere, professor emeritus at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium, compared economics, environmental impact and ethics of three of the most widely accepted alternatives during a panel discussion at VIV Europe 2022.

Alternatives to day-old chick culling

3 solutions have been proposed as alternatives to chick culling:

raise the hatched male layers for meat,

switch to dual-purpose breeds that produce both meat and eggs, use in-ovo

sexing technology to determine gender before eggs hatch.

Each solution addresses societal concerns around the culling of day-old chicks. Individually, however, they present challenges in terms of economics, the environment and ethics.

Raising male layers

In northeast Germany, a 19-farm organic producer group called EZ Fürstenhof has been working to eliminate male chick deaths entirely for years. Founded and managed by Friedrich Behrens, EZ Fürstenhof produces eggs and meat from the “haehnlein” or “brother hens”.

According to Behrens, though, Haehnlein take four times longer than typical broiler breeds to reach maturity, which means added costs for feed and resources. On a visit to his farm in 2018, Behrens said each bird would need to be sold for €32 just to cover costs. To support this cost, Behrens charged an additional €0.04/egg produced under the Haehnlein concept. Over the lifespan of the hen, the additional fee supports production of the male layers.

Economists like Peter van Horne from Wageningen UR don’t believe the math makes sense, though. In a talk on in-ovo sexing at VIV Europe, Van Horne honed in on the Dutch market, presenting economic and environmental arguments against the practice.

According to field data from the Netherlands, male layers take 98 days to reach a weight of just 1.5 kg. Of that, just 17% is breast meat. The male layers in the study had a feed conversion rate of 3.5.

Conversely, commercial broilers take just 42 days to reach a live weight of 2.4 kg and have 25% breast meat and a feed conversion rate of 1.6. At current feed prices, Van Horne estimates an additional cost of €4/per male layer.

Adopting dual-purpose breeds

Adopting dual-purpose breeds

Switching to dual-purpose breeds would also impact egg production. By Van Horne’s calculations, the industry would require 39 million hens to lay the same number of eggs as the 33 million highly productive hens they would be replacing. The transition would cost the industry an additional €286 million, said Van Horne, adding that male layers require 10% more feed.

“My conclusion is the lowest cost to produce eggs is with modern layer breeds,” said Van Horne.

Then there’s the question of how to market the end product. While the eggs produced under the German Haehnlein concept partially alleviate the financial losses that come with producing lesser quality meat, Dutch slaughterhouses offer less than they pay for spent hens (€0.04/bird). Under a similar system, Dutch producers would have to increase prices by €0.01–0.015 per egg.

“What do you do with this bird? Van Horne asked. “Nobody wants it.”

Using in-ovo sexing technology

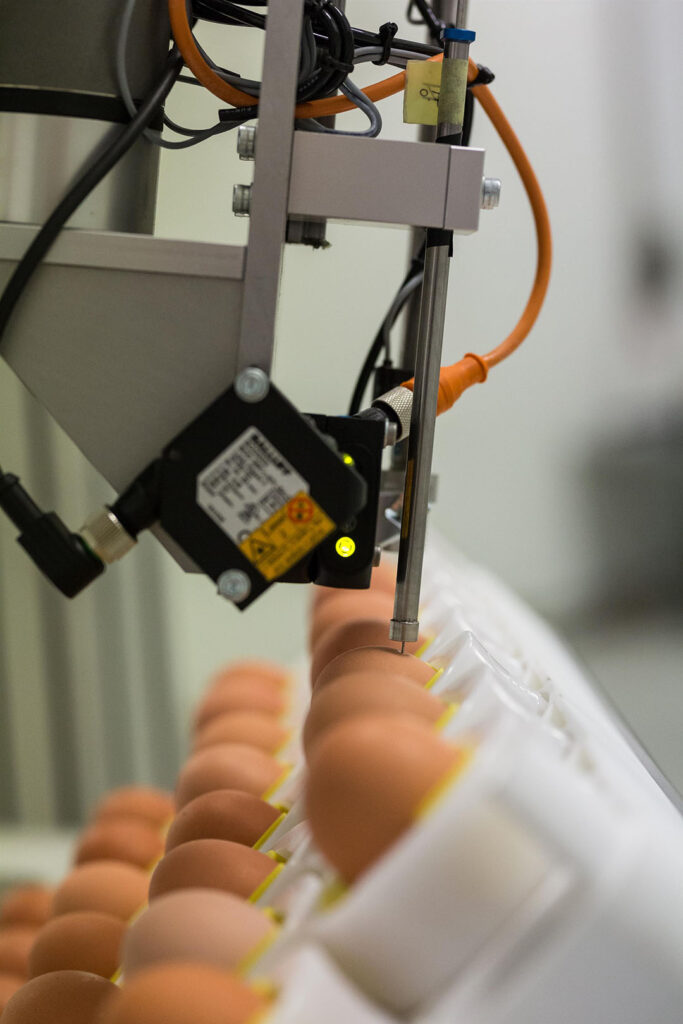

The third suggested solution for ending chick culling is the adoption of in-ovo sexing technology. Currently, there are several solutions on the market. Developed in Germany, Seleggt sexes eggs using endocrinological gender identification. Lasers create a 0.3mm hole in the shell of the egg and, using a tiny needle, a small amount of allantoic fluid is extracted for analysis. Eggs are sealed after extraction and sorted according to results. Seleggt can sample one hatching egg/second or 3,000 eggs per hour. The Seleggt process makes it possible to distinguish between female and male hatching eggs on the ninth day of incubation, but the company would like to reach day-6 identification. Seleggt is designed for 24-hour use and has been on the market since 2018.

Also developed in Germany, PLANTegg uses a small needle to remove allantoic fluid, which is analysed using PCR technology for gender chromosomes. Once sampled, they are sealed and sorted. Female eggs are returned to the setters to continue the hatching process. Sex determination is completed in 1.5 hours. PLANTegg says it is 98-99% accurate.

In May 2022, Orbem and Vencomatic Group announced that they’re working in partnership to market “Genus Focus”, a fully-automated, end-to-end system for sex determination. Their non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) solution determines sex between day 12 and 13 and has a throughput of 24,000 eggs per hour. It can be used with both brown and white eggs. 2 installations with the capacity of 6,000 and 12,000 eggs per hour will be fully operational at 2 French locations in January 2023, operating in line with French regulatory requirements.

Pedro Gomez, co-founder and CEO of Orbem, said the technology offers 4 key advantages when it comes to in-ovo sexing: it is safe for eggs and operators; it is versatile in that it works with all breeds and colours; it’s fast; and it’s 96% accurate.

Carbon footprint

Sex determination comes with additional costs as well, though. In-ovo testing requires equipment to sample and separate, plus the additional cost for disposal of male eggs. Including some margin for error, Van Horne estimates adopting in-ovo sexing technology will cost hatcheries an additional €3.30/bird, which is similar to the cost of growing out male layers. Given current feed prices, however, the cost of growing out male layers would actually be much higher than adopting technology for sex determination, he said.

Once he calculated the environmental cost of each solution, the answer became clear.

Calculating for increased feed and land use, and increased energy consumption, he found the carbon footprint of male layers to be 3 times that of commercial broilers. “It’s very clear there is a negative carbon footprint,” he said.

“It’s also obvious, looking at the environment, that this is not the way to go.”

Pain receptors in embryos

Currently, German law requires eggs to be sexed by day 7, but there is talk of pushing that up one day to address another possible issue: the question of if and when embryos feel pain. Eddy Decuypere, professor emeritus at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium, said the push for day-6 is unnecessary, though. During his talk at VIV Europe, he discussed the ethical questions around pain reception in embryos at the different stages of development.

There must be functional connectivity between the different parts of the brain in order for embryos to be conscious of pain, Decuypere pointed out. While embryos begin to show high rates of movement at day 15.5–16.5, no higher brain activity is present. By day 16.5–17.5, the first signs of higher-brain activation appear with decreasing movement rates as development progresses. By day 17.5–18, all embryos have higher brain activation, and by day 18–21, different brain patterns (waking, REM and NREM) begin to emerge.

While German policymakers push producers towards day-6 sex determination, claiming it’s more ethical than, say, French legislation, which states in-ovo sexing must be done by day 14, the science seems to say otherwise.

“There is no exact date or hour, and it also depends on the criteria for pain perception used, but there seems to be scientific agreement to put it on day 13–15,” Decuypere said.

On the question of moving to earlier and earlier detection, Decuypere laughed. “Forget it. In my view, it’s marketing,” he said. “It’s marketing for companies, it’s marketing for politicians, but it has no scientific basis.”