Reducing sow deaths and supporting better welfare

Efforts to reduce sow deaths and otherwise improve their welfare is in the spotlight in the US, where sow deaths have reached a historic high. How can better staff training and integrating technology solve this serious problem?

First, the numbers. Average sow mortality on US pig farms was already very high in 2023, then rose by 1.6% to 2023, reaching an unprecedented rate of 16.2% last year. That data is from MetaFarms, a Minnesota-based firm. Brad Eckberg, their product subject matter expert, says that the 2023 sow death rate was due to many factors: outbreaks of PRRS (porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome) and heat waves but also the introduction to new group sow housing systems under the US ‘Proposition 12’ legislation.

In other nations, the sow mortality rate is much better. Looking at Canada, analysis was recently published by a team from the Prairie Swine Centre, University of Saskatchewan, the Canadian Centre for Swine Improvement and the Centre de dévelopement du porc du Québec. Looking at 104 Canadian pig farms in various regions and other data, the team concludes that average annual sow mortality in Canada is about two-thirds less than the US, at 5.7%.

Causes of death

MetaFarms has determined that almost a quarter (23%) of US sows in 2023 were caused by uterine and rectal prolapses. Another 24% of deaths were attributable to structure/body condition and 12% to general health issues. Causes of death for the other 34% of the sows, include PRRS, PRRS-related infections and unknown issues.

The Canadian researchers point to higher death rates for gestating sows housed in groups, perhaps due to an increase in aggressive interactions – but as producers become more experienced with this housing (and genetics adjust as well), sow mortality should drop. This will also occur in the US, says Eckberg.

“Studies over the last 12 months have shown higher sow deaths on Proposition 12 farms, due to a combination of nutritional, husbandry and some genetic lines are more robust than others,” he notes. “The group sow housing pens on farms vary in size, which is likely a factor. It’s certainly easier for farm workers to manage sow aggression in smaller pens with fewer sows, and it’s also easier to identify and treat compromised sows. But it’s very costly to create more pens in an existing barn or a new barn, as each pen needs its own water and feeding infrastructure and that means fewer pigs per barn. So we may not see smaller pens at many operations for quite some time.”

Larger herd sizes, which are much more prevalent in the US, are also a likely factor in US and Canadian sow death rates. The Canadian scientists say this might be because “larger farms experience greater staff shortages, with limited time for identification and treatment of compromised sows.” Can this be mitigated with better training and technology?

Programmes in place

Training to identify troubled animals is covered in 2 mandatory US programs, both about a decade old and involving farm audits: Pork Quality Assurance (PQA) and the Common Swine Industry Audit. Proposition 12 audits also began this year.

PQA Plus is an additional program designed to help pig farmers and their employees continually improve food safety, animal well-being, environmental stewardship, worker safety, public health and community. Both individuals and farms can be certified.

All these programmes are updated over time. Eckberg notes that greater use of post-mortem to identify causes of sow death are also needed.

The role of technology

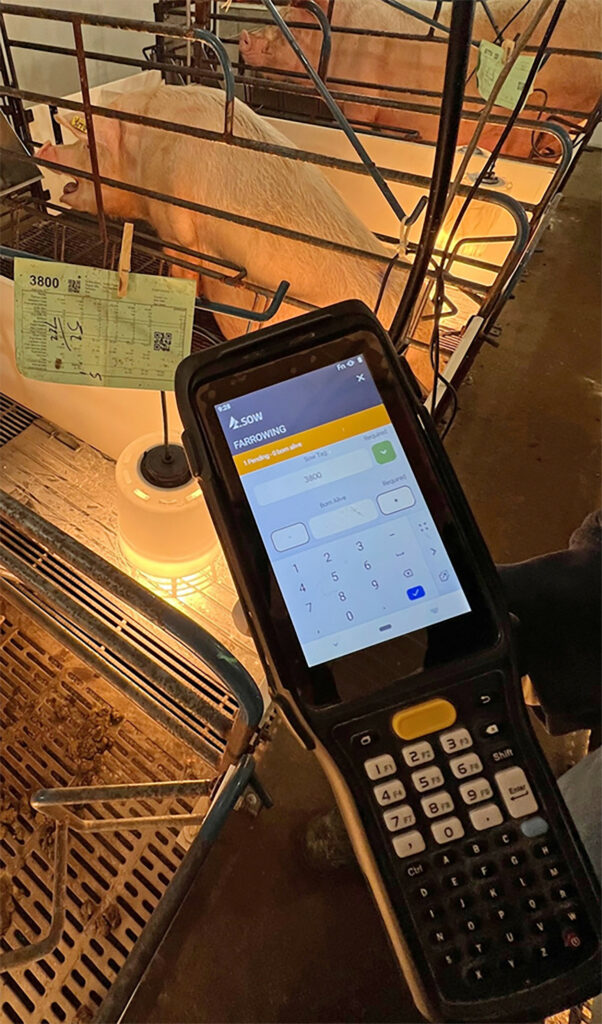

“Technology can be a useful tool,” notes Eckberg. “It can be very useful to see how sows are doing. We cannot depend on it to tell when a sow is going to die, but on a daily basis, we can identify sick pigs, abortions, track sow deaths and can take action a lot sooner. A lot of producers are carefully tracking this, but here’s the thing. About 60% of our customers are using tablets to input data, and the rest are writing it down on paper and then entering the data into their computer system, but that might be the same day, or another day that week, once a week or once a month. So you are not tracking pig health and deaths in a meaningful way. It’s just data entry by tablet or on paper for eventually finding out how many pigs did we wean this month.”

There is therefore a huge opportunity for pig producers to use software that helps analyse data in a timely fashion – and sends alerts, says Eckberg. “If you don’t know the daily picture of sick sows, abortions, deaths, you can’t make those quick necessary decisions about how to solve the problem, how best to move resources around, change in feed and ventilation and water, to act accordingly in a timely fashion to prevent death and maximise sow health and well-being.”

Data can be entered through an app or a phone or tablet, and there are offline capabilities in these apps for data entry where the data will automatically enter the system when in range. The system then analyses the data and send alerts.

These systems can also be connected with ‘smart controllers’ for fans and temperature sensors to send alerts as well. “If there is a chilly draft in a certain part of the barn or it’s getting too warm, you can get alerts and act,” says Eckberg. “A relatively simple automated system can track fan speeds, humidity levels and temperature for pig health and welfare. You can also have bin sensors to ensure feed is flowing and pigs don’t run out of food.”

There is a cost for the subscription fee for these analysis and alert systems, but Eckberg notes that the cost is quite low in comparison to the cost of dead sows, which range from USD$300 to $350 each.