Insects-for-feed production in Africa

The number of insect farms is expanding in Africa, however there are still several barriers holding back the production. The right approach is needed.

Insect farming for feed in Africa is rapidly expanding, with large numbers of new farms registered in 2023, according to scientists Dr Chrysantus Tanga and Dr Margaret Kababu at the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICIPE) in Kenya. Tanga and Kababu note that most countries in Africa already have insects-for-feed production.

Their findings are outlined in a paper called ‘New insights into the emerging edible insect industry in Africa,’ published in the journal Animal Frontiers. Tanga and Kababu point out many benefits of insect production for feed, including reduced need for imports, recovery of otherwise-lost food waste, frass (insect waste) fertiliser, and sustainable jobs.

Insectipro

Among the many African companies that have started up production of insects for animal feed is Insectipro in Kenya. There, it is currently processing over 120,000 tons of food waste a year to produce 11 megatons of dry black soldier fly (BSF) larvae, which feeds 9 million chickens annually.

“At least 80% of our production still goes towards animal feed processors and about 90% of our frass (insect waste fertiliser) production goes to small-holder farmers,” says a company spokesperson. “At the moment our biggest challenge is funding, as well as access to enough eggs.” Once the company has raised the funds, Insectipro plans on expanding into multiple countries in Africa over the next few years.

“Besides that,” says the spokesperson, “teaching the market on the frass product is also a big challenge, which we have worked on a lot last year. You also need time, time to figure out the entire process and business model because at the moment we started, there was very little information available.”

Research into insect production

On the topic of research into insect production from food waste, a large amount has been completed in recent years under the Insects-as-Feed West Africa project. Although the project is no longer active, under its co-ordinator Dr Marc Kenis, dozens of scientific papers, resource documents, training courses and videos were produced, all still available on the website. Studies spanned the countries of Benin, Burkina Faso and Ghana.

There are also modular insect production systems. Modularity in any process means you can start with 1 or 2 modules at a small scale and cost, and add additional modules added as desired. Flybox is a UK-based insect farming module manufacturer with a project in the Constituency of Kiambu, a town near Nairobi, Kenya. Here, a Flybox system is being used to convert municipal market organic waste into BSF larvae for feed.

“We have now evolved this project to an upcoming fertiliser scheme where the fertiliser will go back to local farmers as part of an initiative in Kenya to switch to natural fertilisers,” says Flybox Co-Founder Larry Kotch. “So, the frass has become the star of the show there.”

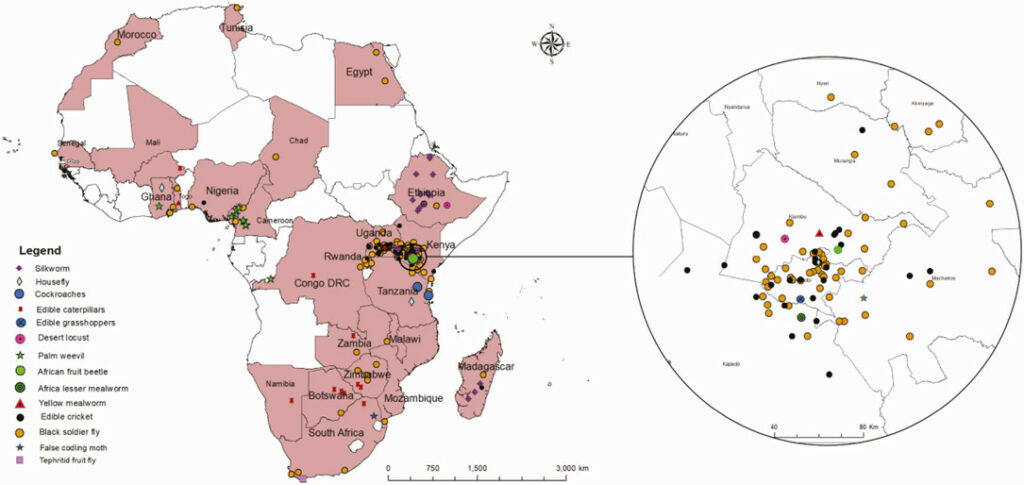

Distribution of semi-domesticated and domesticated edible insect species in Africa. Countries with white background have no insect farming activities and those shaded with maroon color have operationalised insect farms for food and feed.

Barriers to growth

There are several barriers holding back insects-for-feed production in Africa and elsewhere. In their paper, Tanga and Kababu point to the need to establish regulations and policies along the value chain to ensure sustainability and safety for consumers and the environment. They note that Africa’s regulation of the section is still in its infancy and requires urgent attention, with “regulatory frameworks on the utilization of insects as food and feed in many countries still lacking.”

At the same time, they add that the “realisation of food safety regulations on edible insects has been hampered by a wide array of factors such as limited compliance with international agreements on food safety and quality standards, inadequate enforcement of local, regional and international standards and global best practices; lack of large-scale industrial production of insects to supply and meet the growing demand by the food and feed sector,” and other factors.

There is also a need in their view for research into the pharmacological and therapeutic properties of edible insects that could improve livestock and human health, obviously adding further value to insect production.

Small-scale production

In recent years, ICIPE staff have worked with local government officials in various African countries to establish pilot farms with simple, locally-fabricated processing machines such a grinders for food waste. These projects have included youth and women incubation programs with mentoring and personalised one-on-one hands-on training on various topics related to insect productions.

“These programs allow for exchanges between insect farmers within or from other countries to visit these pilot facilities and learn insect rearing and processing, pest and disease management and facility and equipment operations,” state Tanga and Kababu. “These efforts are done in collaboration with universities and other research institutes. The pilots or demonstration or learning sites help to promote insect-based value-added products through exhibitions and media coverage events to raise the much-needed public awareness campaigns on the insect sector’s value and benefits to the continent as a whole.”

However, Kotch believes this approach is not the one to take.

Training is pointless

In Kotch’s view, grant money being spent on training farmers to try and farm insects is going to waste. He notes that the vast majority – about 90% in his view – of these people fail at insect farming from food waste for 2 simple reasons.

One is that they receive no (or very little) follow-up support after initial training.

Secondly, achieving successful insect farming means achieving successful breeding (egg laying). That process is quite complex and much easier to do in a specialised facility – a hatchery, if you will.

A new approach

Here is the model of insect production for feed that Kotch proposes instead – one with manure as the feedstock and not food waste:

The smallholder regularly receives a mixture of eggs and juvenile larvae (called seedlings) on his or her farm, similarly to how chicken farmers regularly receive chicks from the hatchery. The farmer adds these seedlings in pre-set amounts to trays of livestock manure. Kept in steady conditions, the larvae consume the manure and grow. At the end of the growth cycle, the farmer separates them from their frass and any remaining manure, and the larvae become fresh live feed for the farmer’s livestock. Feed for livestock that’s produced through consumption of their own manure – a rather perfect circular food and feed production concept.

Kotch notes that “this is the main advantage of the Kenyan, and now East African, legal regime with insect production” – that is, that on-farm manure upcycling back to feed is legally allowed in these countries. He notes that this changes the economics of insect farming completely, making it in these jurisdictions “probably twice as good as in Europe.” Flybox is currently building such a ‘hatchery’ for a customer in Uganda who will supply local farmers with BSF eggs/seedlings.

Looking forward

As to why there are attempts to train farmers to farm insects with the breeding cycle included and using food waste as the substrate, Kotch says “my sense is that the development funding agencies love the impact story and the natural logic of insect farming but don’t appreciate the difficulty of doing it economically. They believe ‘training in insect farming’ is the solution and they are wrong. I hope people wake up before too much money gets lost…Development agencies would be better off subsidising seedling costs than throwing money at training which is done by organisations that are not economically-minded a lot of the time.” He believes that new manure-to-live feed project in Uganda is slowly helping to wake people up. Besides adoption of separate hatcheries that supply local farmers for manure-to-live-feed production, the other main thing needed for the on-farm ‘manure upcycling to feed approach’ is standardised larvae growing systems. To help with this, Flybox is developing a low-cost ‘smart’ polytunnel structure (plastic ‘poly’ on a frame) with basic sensors that will enable farmers to provide consistent environmental conditions to achieve efficient larvae growth.