Choices, choices: Making the most of available by-products in animal feed

Over the past couple of years, the availability of novel by-products for animal feed has increased, notably with the increased availability of waste materials from the biofuel industry such as distillers dried grains and soluble (DDGS). The usefulness and affordability of ethanol by-products for the feed and animal production industry is now familiar, especially where the economic situation in some countries means increased pressure on feed and production prices for animal products.

By Dr Jules Taylor-Pickard, global Mycosorb manager, Alltech Global Headquarters, Kentucky, USA

DDGS is a major by-product from the processing of plant material to yield ethanol. This raw material is suitable for feeding to many species, and offers high levels of crude protein and certain minerals, due to the concentrating effect of ethanol production.

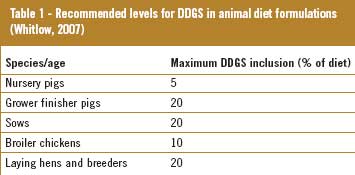

DDGS can be used in animal feeds to partially replace corn or soybean meal and even sources of phosphorous in formulations. The inclusion of DDGS in animal feed can often be limited by several factors, including variability in nutrient composition, spoilage, quality of source material, processing methods during ethanol production, preparation of the final product, storage facilities and quality control systems. Although initially the nutrient profile (e.g. protein) may look very useful, care must be taken in making any assumptions about the true amounts that are available, as digestibility may be surprisingly low.Due to its variability and the risk of mycotoxin contamination, the recommended use of DDGS in animal feed has been limited (Table 1).

Variability

Variability is a major issue that affects the nutritional value of DDGS. In the US, many ethanol plants adhere to good levels of QC, leading to better quality DDGS; however, this attention to detail is not universal across regions or even manufacturing plants. Some countries have already been implicated in producing very poor quality by-products, which may contain dangerous or prohibited materials due to differences in processing and preparation conditions. Variability in nutrient profile (Table 2) and digestibility means that formulating DDGS into animal diets must be done carefully, and ideally each batch needs to be evaluated before it is used. Alternatively, companies producing DDGS may take it upon themselves to impose high standards of QC, enabling them to sell a more ‘quality guaranteed’ co-product (as opposed to an uncharacterised by-product) to the feed industry. An appropriate way to resolve variability and nutrition issues with DDGS is by the application of a suitable enzyme that is able to maximise the nutritional benefits to the animal from this feed material. Recent research has proven that laying hens can be fed 20-25% high-quality DDGS in their diet without loss of performance. Broiler trials have also been conducted to investigate the potential upper limited of inclusion, and have found that up to 15% of high-quality DDGS may be included with no loss in performance or meat quality. Grower-finisher pigs can tolerate levels of 30% in feed, but some changes in meat quality were observed. In all cases, the addition of a suitable and proven enzyme is highly beneficial in maintaining and optimising animal growth and performance.

Feed trials

Trials using enzymes alongside increasing levels of DDGS in commercial feeds have recently shown benefits in performance. Grower-finisher pigs have been assessed in their responses in a trial using 10, 20 or 30% DDGS in the diet with or without Allzyme SSF* (ASSF; Alltech Inc.). Between days 1-111 of the trial, the average daily gain of pigs fed the 30% DDGS diet was severely reduced from 0.86 kg/d down to 0.82 kg/d – a loss of 40g of liveweight – and saw a reduction in backfat, loin depth and ham muscle levels. Including ASSF in these diets restored all the performance parameters back to the level of the 10% DDGS diet (Figure 1).

A further trial conducted in the US at Virginia Tech University showed that phosphorous (P) digestibility in crossbred pigs fed a corn-soy based diet had higher ileal digestibility of P when supplemented with ASSF, which was identified as a linear response to the dose of enzyme (100, 200 or 300 g/t). When the total P in the diet was correlated against average daily gain, a strong curvilinear relationship was found (R2=0.89), indicating that the increased release of P was influencing the ADG up to a plateau of maximised performance (Figure 2).

By-products for ruminants

For ruminant species, several other feed materials have made an appearance on the commercial markets in recent times. These include glycerine (glycerol), again as a by-product from the biofuel industry. Glycerin is available from the biodiesel industry in varying grades of purity, so variability is still a key issue. However, in ruminants the net energy (NE) value of glycerol (2.27 to 2.31 Mcal/kg dry matter) was equal to or greater than that of corn grain. NE values were approx. 13% lower in high-starch diets (about 1.98 Mcal/kg) than in lower-starch diets, due to decreased cell wall (NDF) digestibility in the presence of glycerol to the higher-starch diets. This means that the economic value of energy from glycerin is comparable to corn grain after correcting for the glycerol content (analogous to the DM of the glycerin) of the material. German research has shown that up to 10% of the dietary dry matter could be supplied as glycerol with no losses in feed intake or performance in growing ruminants or lactating cows.

Similarly, feeding experiments with growing chickens showed that 5% addition of glycerol did not affect growth or feed efficiency, but the addition of 10% slightly decreased performance. Similar responses were reported by South Dakota researchers who found that glycerol for transition cows decreased dry matter intake before calving.

Methanol residues

Other concerns with glycerin as a feedstuff are regarding its methanol and mineral salt levels, although pelleting seems to remove any methanol remaining in the material. Contributions to mineral intake by glycerin might be a factor in dry matter intake and need to be accounted for in the diet. The high phosphorus content also is a concern in nutrient management plans. The current data indicates that, overall, a 10% inclusion of glycerin is considered appropriate for use in dairy cow diets.

Mycotoxin risks

Other by-products that are rising in popularity include palm kernel meal (PKM) and copra, which are used as fibre and oil feed sources, especially for dairy cows. As with the DDGS, moist feed materials that are poorly stored are at high risk of mycotoxin contamination via fungal growth, and should be careful handled and stored to prevent this. Ensuring the use of a suitable mycotoxin binder is essential where the quality of the material may be in doubt. EU import data regarding alternative feed materials from 2008 show that the consumption of copra was 16,000 t and PKM was 2,344,000 t. In some parts of the world these fibrous by-products have become the main feedstuff alongside grazing. This has caused some issues regarding mineral balances as well as the quality and variability of the material. Once again, the use of a suitable enzyme and a mycotoxin binder to ensure maximal digestion and nutritional value as well as safety would be the best strategy for using such materials in finished feeds and daily mixed rations. In a world where animal feed increasingly competes with human food for raw materials, alternatives have to be sought by nutritionists and producers. In order to maintain a supply of safe, digestible feeds, by-products must be used in conjunction with stringent quality control procedures with precautions taken to minimise contaminants, such as by supplementing with mycotoxin binders together with digestive-enhancing enzymes to enhance nutrient release.

*Allzyme SSF is not available for sale within the European Union.