Diet and gut health influence tail biting in pigs

Tail biting continues to be a major health and welfare challenge in commercial pig production with diet being a major risk factor. Researchers from Denmark have studied the link between a pig’s diet, gut health and mood, and have uncovered some interesting results.

Tail biting is a pathological behaviour that can be seen particularly in weaners and grower-finishers in commercial pig production systems. Tail biting can result in pain and infection by the bitten pigs, and can create stress within a group of pigs, and is, therefore, a major health and welfare concern.

Although this challenge is multi-factorial with various management and housing factors increasing its risk, the European Commission summarises the following as the key risk factors for tail biting:

- Enrichment

- Climate

- Health and fitness

- Competition over resources

- Diet (feed composition and quality, amount consumed, form, phase-feeding strategy, poor accessibility)

- Pen structure/cleanliness

A study conducted by researchers* at the Department of Animal Science at Aarhus University in Denmark aimed to review possible but still mainly unproven risk factors of tail biting in growing pigs related to feed composition and feed supply and their interplay with gut health and behaviour through the microbiota-gut-brain axis.

“While lack of enrichment is known to cause tail biting via an unfulfilled motivation to forage and explore, the mechanisms behind diet-related risk factors are still not clear. Research from the last decades on the existence of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain-Axis in mice, rats and humans may help us understand the mechanisms of how diet-related factors leads to tail biting and thus offer ways to mitigate it. Accordingly, studies are now emerging indicating a link between the gut microbiota and tail biting.” – Cecilie Kobek-Kjeldager

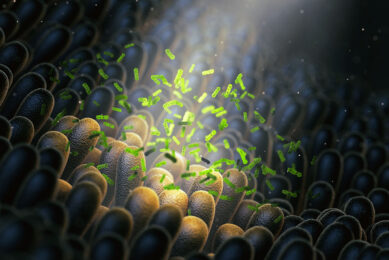

The microbiota-gut-brain axis

Much research has shown a complex, bidirectional communication between gut microbiota, intestinal health, and the brain, affecting mood and behaviour via the so-called microbiota-gut-brain axis.

Dysbiosis, or an imbalance in the composition of gut microbiota, is largely mediated by dietary factors and plays a role in many pathologies including those related to the brain, mental state and behaviour. It can be concluded, therefore, that diet plays a major role in affecting this axis and is therefore hypothesised to have a significant effect on tail biting.

The feeding factor

This study looked closely at the diet and suggests that diet-related risk factors for tail biting are under- and oversupply of protein (including tryptophan), lack of satiation, fine feed particle size, low dietary fibre content and a limited number of feeder spaces.

These factors can cause social stress, gastric ulcers, dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, disruption of the intestinal epithelium, and affect the animal’s stress sensitivity via the microbiota-gut-brain axis, which can cumulatively lead to tail biting.

Protein and amino acid imbalances

The Danish researchers note that feeding diets with too low dietary protein levels, an imbalance in the essential amino acid composition and/or mineral deficiency may increase the occurrence of damaging behaviours such as ear-biting and tail biting.

Being protein-deficient impairs the pig’s resilience to cope with stressors and predisposes behavioural depression signs and aggression and increase foraging motivation, which increases the risk of tail biting via increased exploratory motivation and tail-mouth behaviour. Meanwhile, an oversupply may increase anxiety behaviour.

Furthermore, mineral deficiency may increase attraction to blood (due to blood’s content of protein and several minerals), accelerating a tail-biting outbreak when the skin has been broken.

The research team believes that adequate amino acid levels including tryptophan, and the inclusion of certain dietary fibres in the diet exceeding levels in standard diets, may stimulate the establishment of beneficial gut microbiota (e.g., microbial diversity and short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria) that protect against inflammation and increase stress resilience.

Optimal levels of tryptophan

Tryptophan is a precursor of serotonin, which is an important neurotransmitter involved in many processes including mood, stress sensitivity, regulation of gut motility, appetite, immune function, sleep and memory. Tryptophan metabolism is modulated by gut microbiota, and an excess of tryptophan can also be metabolised into potentially harmful substances. So, the researchers note that careful consideration is needed in future studies investigating whether the optimal tryptophan level for gut and mental health differ from levels for optimal growth.

The role of antibiotics

Antibiotics are a useful and necessary tool to combat specific bacteria that pose a risk of tail biting, but antibiotics can also disturb the gut microbial balance, which in turn increases the risk of tail biting.

Conclusion and considerations

In conclusion, while tail biting is multifactorial, the researchers suggest that an imbalance in the microbiota-gut-brain axis, modulated via the diet, should be considered as a pathway for the development of tail biting, but needs more research. The team, led by Cecilie Kobek-Kjeldager, suggests a whole-animal approach, including considerations on gut health, satiety, beneficial gut microbiota and an adequate feed supply avoiding social stress to mitigate tail biting.

*The research team included Cecilie Kobek-Kjeldager, Anna A.Schönherz, Nuria Canibe and Lene Juul Pedersen from the Department of Animal Science, Aarhus University, Denmark.