How does zero grazing measure up?

Climatic conditions, whether too wet or too dry, are often the deciding factors that persuade dairy farmers to use zero grazing as a management tool.

If the country is too hot, cows might be affected by heat stress. Zero grazing is a possible solution. Likewise, if the climate is too wet in a region, grazing cows could do a lot of damage, leaving zero grazing as the only option. That is part of the dilemma many farmers face when deciding which feeding method is best suited to the conditions of their farms.

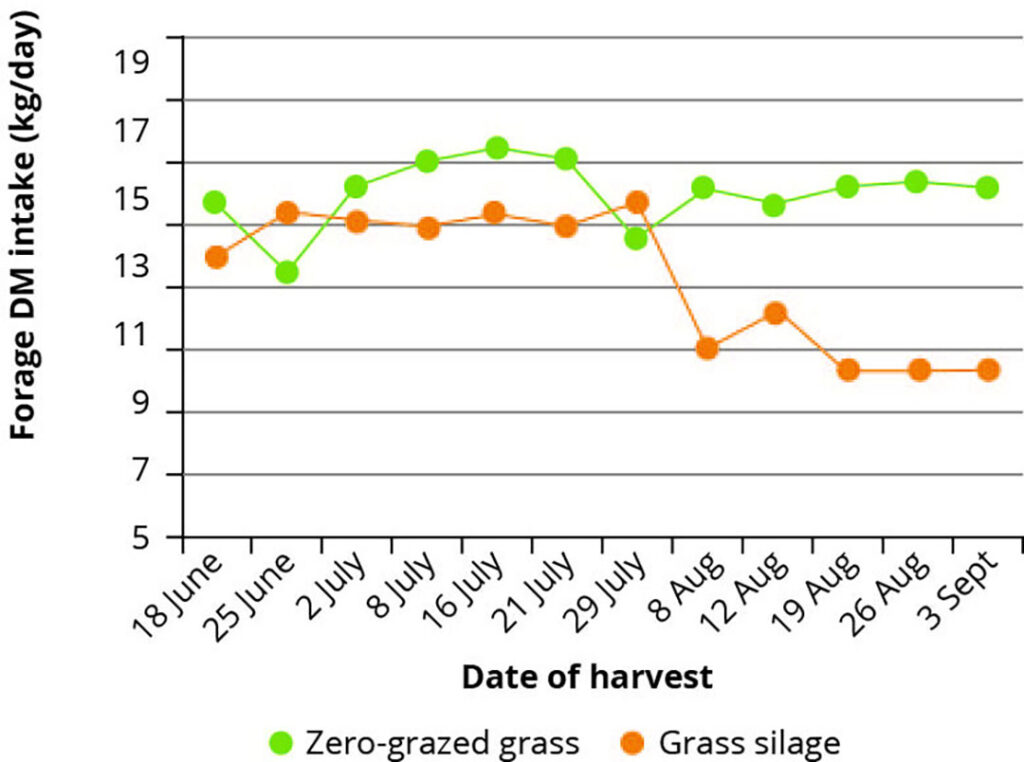

Figure 1 – Average weekly forage dry matter intake of cows offered zero grazed grass or grass silage produced from the same sward.

Reasons for zero grazing

There are a number of other reasons for carrying out zero grazing on a dairy farm. For example, farms may have blocks of grazing land in different areas, making it difficult to walk cows long distances to get to them.

Another reason is that there could be too many cows in the herd to walk them all at once to fields. Fresh grass can also boost milk quantity and quality when fed to housed cows during summer.

As grass is the cheapest form of feed for a dairy herd, zero grazing could be a better option when other feed costs increase – depending on the cost of harvesting and hauling the grass to the cows, of course.

Advantages

Higher dry matter (DM) intakes with fresh grass

Utilisation of grass more efficiently and extension of the grazing season

Better use of fields that are too far to walk cows to

Relative cheapness of grass means that using more of it reduces feed costs

Freeing up of land to grow other feed on

Disadvantages

Can require extra labour and machinery costs to harvest and haul

If weather is bad, harvesting can be difficult

Grass cut in the afternoon will have higher sugars and lower free nitrogen and fibre.

Is feeding silage a better option?

Whatever the reason, zero grazing is becoming very popular on many dairy farms across the world, but could feeding silage instead be a better option?

Recent research by Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI) in Northern Ireland has shown improved performance from cows offered zero-grazed grass compared to grass silage.

Silage study

As it may be difficult to maintain a sward at the optimum quality for zero grazing throughout the season, AFBI asked how cows would perform if offered silage produced from a sward at the same stage of growth as is normally harvested for zero grazing. Offering very high quality silage, instead of zero grazing, could have a number of possible advantages, including reducing the need for harvesting to approximately once every four weeks compared to daily for zero grazing systems.

Silage production is more weather dependent, and ensiling young leafy herbage can be challenging, especially later in the season. The study was conducted over 12 weeks between June and September in 2020. Fresh grass for zero grazing was cut daily and offered to a group of 18 mid-lactation dairy cows. Grass for silage production was cut once per week, from the same sward where zero grazing took place.

Weather permitting, grass was tedded to facilitate wilting, with a target DM at ensiling of 25–30%. Grass was ensiled in round bales with no additive applied at ensiling.

Following a five-week storage period, silage was offered to a second similar group of 18 cows for 12 weeks. Cows in both groups were offered 8 kg concentrate per day via an out-of-parlour feeding system.

Study result

The zero-grazed grass had an average DM content of 15.6%, while the grass silage had an average DM content of 27.3%. The silage had a slightly lower crude protein content than the zero-grazed grass, reflecting loss of protein during ensilage. However, both forages had a similar metabolisable energy and fibre content, indicating that both were harvested at a similar stage of maturity.

Intakes of zero-grazed grass were higher than intakes of grass silage, with intakes of silage produced between 30 July and 3 September being especially low, reflecting the challenges of ensiling leafy herbage later in the season.

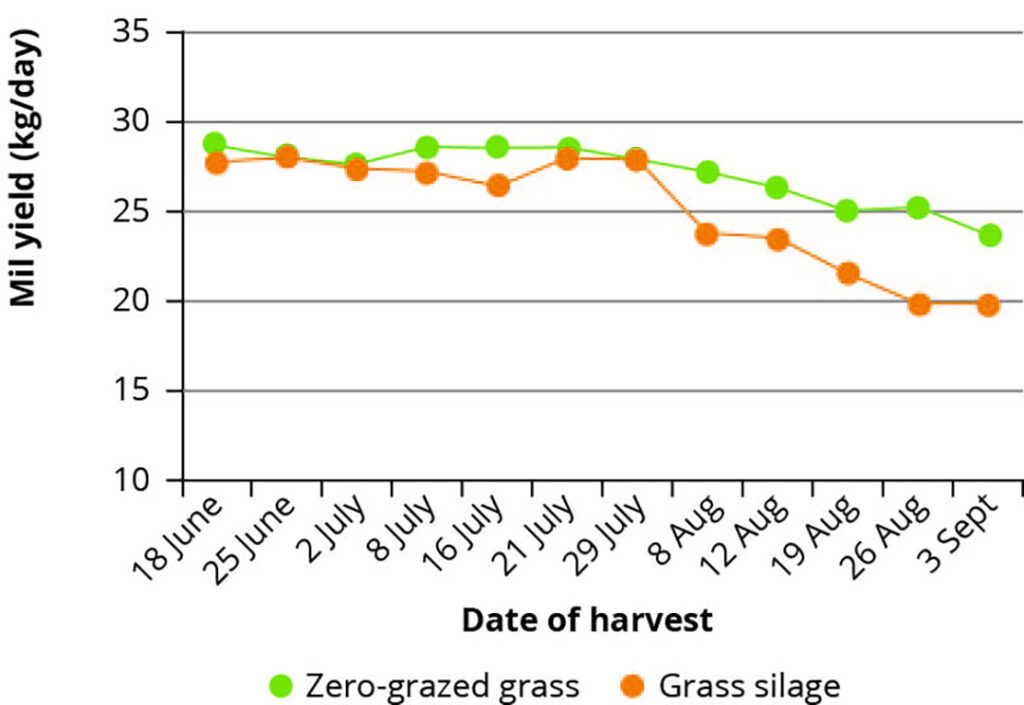

Milk yields followed a similar trend to silage intakes, being relatively unaffected between treatments earlier in the season, but then decreasing more rapidly with the silage treatment later in the season.

While milk fat content was unaffected by the forage type offered, the types of fat in the milk differed. For example, cows offered zero-grazed grass produced milk with higher concentrations of “healthy” fats (monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats) than those offered grass silage.

In addition, the concentration of conjugated linoleic acid, a fat believed to have anticarcinogenic properties, was higher in milk from cows offered zero-grazed grass.

Cows offered zero-grazed grass also produced milk with a higher protein content, likely reflecting improved supply of protein from the rumen bacteria. The fat plus protein yield was higher from cows offered the zero-grazed grass throughout the experiment.

Cows offered zero-grazed grass had higher forage DM intakes, milk yields, milk fat plus protein yields and a higher milk protein content compared to those offered grass silage prepared from the same sward. In addition, these cows produced milk containing “healthier” fats.

The differences in intakes and milk yields were particularly apparent later in the season, during August and September, which is likely to reflect challenges of ensiling herbage at this time.

Figure 2 – Average weekly milk yield of cows offered zero grazed grass or grass silage produced from the same sward.

Conclusion

Given the current cost of fuel and concentrate feeds, optimising the inclusion of grazed grass in dairy cow diets offers the lowest cost strategy by which to produce milk.

AFBI recognised that many farmers continue to demonstrate that well-managed grazing systems can sustain high levels of both physical and economic performance.

However, it did say systems with a major focus on grazing are no longer practised on many farms. In these situations the current study has demonstrated that offering zero-grazed grass increased forage DM intakes, milk yield and milk fat plus protein yield, compared to grass silage prepared from the same sward at the same growth stage.