Climate assessment for farmed salmon

Climate awareness is a growing issue worldwide and agriculture and aquaculture need to acknowledge their responsibilities towards this. To test the CO2output from aquaculture, a life cycle assessment study was carried out by the Swedish Institute for Food and Biotechnology (SIK).

By Emmy Koeleman

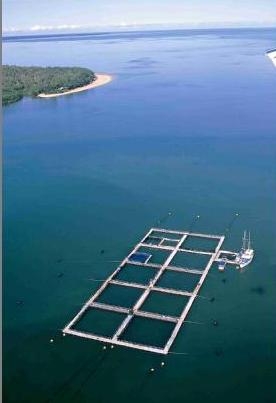

The Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) was commissioned by fish feed producer Skretting and looked at the total carbon dioxide emission from farm to fork. The study involved salmon farmed in Norway and shipped to Stockholm for consumption.

It began with the raw materials used in the feed (both agricultural and from fisheries), feed production and transport, fish farming and processing, transport to the wholesaler and retailer and then to the consumer, ending with preparation of a salmon fillet in the consumer’s home. Through this sequence, the study quantified all emissions that contribute to global warming, acidification and eutrophication and all electricity and fuels consumed.

Comparison with pork and beef

SIK is an independent research institution that is a world leader in Life Cycle Assessment. Through previous studies, the institute has collected comparable data from chicken, pork and beef production. “This study shows that salmon produced in Norway have almost the same volume of CO2 emissions per kg meat as chicken, which is half of the CO2 emissions from pork meat production and less than a seventh of those from beef production,” according to Trygve Berg Lea, International Product Manager in Skretting. The comparisons are based on the food’s Global Warming Potential (GWP). GWP is measured in actual CO2 output plus CO2-equivalents in which the climate impact of other greenhouse gases, for example methane, is expressed as the amount of CO2 that would cause the same impact. The study revealed that salmon’s GWP was 2 kg CO2-equivalent per kg salmon fillet.

Feed is biggest contributor

The study shows that salmon feed production contributes 80% of the total emissions. Berg Lea explained: “On the one hand, this shows us that if we want to improve the salmon’s GWP, then the feed would be the right place to start. However, we must not allow ourselves to be blinded by figures either.

The reason why the percentage of greenhouse gases is so high for feed production is because the fish farming phase and the activities that come after feed in the value chain produce very little greenhouse gases.” Another interesting finding in the study is that the GWP accounts were not noticeably affected by using a feed with a low fishmeal content compared to a feed with a fishmeal content equivalent to a normal Skretting diet. “We were aware that the marine raw ingredients in the feed contribute significantly to the salmon’s GWP, but the study also shows that use of vegetable raw ingredients results in greenhouse gas emissions. This shows just how complex it can be to decide whether a product is “eco-friendly”. A sustainable feed with a low content of marine raw ingredients does not necessarily need to be a greener feed,” Berg Lea said.

Conclusion

The study involved salmon farmed in Norway and shipped to Stockholm for consumption. It would have had a more favourable result for salmon if it had been consumed in Norway and a less favourable result if it had been consumed in another European country. However, even if the finished salmon product had been sent to a Central European country for consumption, the affect would not have been more than a 20% increase, i.e. that the emissions would have been 2.4 kg CO2-equivalents, which is still much less than for pigs and cattle.

Feed tech Vol. 13 No. 5, 2009