Wheat dictates DDGS supply in Europe

Only one tonne of ethanol can be produced from 3.3 tonnes of wheat. Many co-products arise from the raw materials used in the process of producing ethanol, the major one being distiller’s dried grains with solubles (DDGS). Other products are carbondioxide and glycerine. In August, Adisseo, in cooperation with Ajinomoto Eurolysine, organised a mini-symposium on the subject in Strasbourg, France.

By Dick Ziggers

‘Variability and nutritional values of DDGS’ was the

subject of the presentation made by Cécile Gady, feedstuffs research manager at

Adisseo. From an earlier discussion it was already clear that feed millers need

a more precise definition of the nutritional content of the DDGS they are

buying. This will be a difficult task since the manufacturing process at the

ethanol plants is far from uniform. On the one side, DDGS quality depends on the

grain quality and/or starch quality that is used.On the other side, ethanol

fabrication adds variabilities such as pre-treatment effects, exogenous

additions of enzymes and yeasts (to ferment the starch), yeast quality, quality

of the recycled solubles, as well as drying temperature and time.

Gady begins her presentation with the

conclusion that bioethanol by-products are derived from complex processes

involving several sources of variation. “It then looks obvious to qualify DDGS

as variable byproducts,” she said. “But what are the nutritional specificities

of these by-products and what exactly do we mean by variation? Are we able to

deal with this variability?” Quite some questions to discuss. Research has shown

that considerable differences are observed among true amino acid digestibility

of corn DDGS samples. Also, the nutrient composition varied substantially among

DDGS with the greatest variation being found for the digestibility of lysine.

Also, the metabolisable energy content of corn DDGS in poultry is more

controversial. Recent estimates of energy are substantially higher than values

reported in the NRC (1994, AME 2480 kcal/kg). Studies in broilers and turkeys

show differences varying from 350 to 425 kcal/kg higher values.

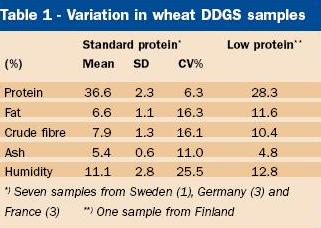

DDGS originating from wheat is

not different in variability than its corn counterpart. Table 1

illustrates the differences in wheat DDGS obtained from different parts of

Europe. Table 2 shows the variability in amino acid

| |

content and true

amino acid digestibility in poultry. Here it can also be concluded that there is

a high variability. Data on the metabolisable energy content of wheat DDGS is

more controversial. Recent estimates of energy are substantially higher than the

value reported by French research institute INRA (2004). Values vary from as low

as 1,820 kcal/kg (INRA, broilers) to as high as 2,676 kcal/kg (Arvalis,

roosters). However, Gady said that measurements are mainly affected by the

methodology applied, as well as the use of unclear and out-of-date product

segmentation.

In conclusion, it becomes clear that for

wheat and corn DDGS there is large variability in crude fibre, fat, ash, lysine

and tryptophan, and also low lysine and cystine digestibilities with high

variability. For wheat DDGS there is a lack of work on energy digestibility, and

for corn DDGS there is lack of consensus on energy digestibility. “A possible

explanation for this is the addition of recycled solubles in different

proportions,” said Gady.

| |

Differences in processing

technologies and conditions, such as possible heat damage, also contribute to

variation. Furthermore, there could be interactions with enzymes and yeasts that

are added during the process. Composing a feed recipe is therefore difficult.

“Nutritionists need consistency and predictability in the feed ingredients,” she

said.

NIRS maybe a solution

A promising technology that could

predict variability fast and accurately is NIRS. Here, a coherent database needs

to be established that is useable for corn and wheat DDGS. Laboratory data and

NIRS data perfectly match in a linear way, with a balanced distribution of

outcomes. Adisseo research showed good NIRS calibrations of total amino acids

(R2>95%) and of amino acid digestibility (R2>80%), except for digestible

tryptophan (R2=66%). Prediction errors associated to the models vary from 2 to

6%, except for digestible lysine (E=9%). Gady’s general conclusion is that

although the ethanol process will further evolve, this evolution will have a

direct impact on the quality of DDGS both now and in the future. The industry

will continue to generate variable by-products, even if efforts are

made for

standardising production.

Consequences for the market

The shift in market demand for cereals

for fuel instead of feed has implications for feed formulators. Figures for 2006

show that cereal utilisation exceeded production. This shortage was then

balanced using the

| |

cereals in stock, which resulted

in a world stock that decreased rapidly. For 2007, utilisation and production

are in balance, but stock cannot be replenished, except on a regional level. On

the other hand, the world market for protein-rich feedstuffs is in a continuous

increase and will reach 250 million tonnes in 2007/08. According to trading

specialist AC Toepfer Int., soybean meal is the main source of vegetable

proteins followed by rape/canola, and then corn gluten feed/DDGS. There will be

a shift in protein sources in Europe in the coming years. Total oil meal and

expellers is expected to increase from 45.2 million tonnes in 2004/05 to 48.8

million tonnes in 2010. Within this group of raw materials there will be less

soybean meal, more rape seed meal, less sunflower and a significant rise in DDGS

availability (Table 3

).

This shift, together with the developments in the biofuel sector, will have

economic consequences. Piet van der Aar, managing director of Schothorst Feed

Research in the Netherlands, summarised the effects of the biofuel industry on

feed formulation. “Biofuels set the price,” he said. “Cereals will be prised at

a higher level and starch sources will become scarcer. The availability of

protein sources will change and higher feed costs are expected. The energy value

of raw materials will become more important and variation in quality should be

known,” said Van der Aar. He also pointed at the increased availability of

rapeseed meal and expellers from the biodiesel industry. Furthermore, glycerol

is a new ingredient which the feed industry is unfamiliar with dealing with.

| |

Price competition

As we can already see today, there is a

strong price competition in raw materials in concurrence with price fluctuations

of crude mineral oil. A higher oil price implies a higher price to be paid for

cereals to be used for biofuel production. For example, if the oil price is $60

(per barrel) the biofuel industry can pay $4.30 – $4.60 per bushel of maize

($175/t) to make a $0.33 litre of vegetable fuel. If the oil price rises to $70,

a bushel of maize can be purchased for $5.40 – $5.70 ($220/t) and vegetable fuel

price increases to $0.36 per litre. It goes without saying that this is tough

competition for the feed industry.

Nutritional effects

Because the fuel industry extracts a

lot of starch from the market, protein will become relatively cheaper. This will

result in higher protein concentrations in diets and will also increase the

risks of more gastro-intestinal disorders in animals. More protein also has a

negative effect on nitrogen and ammonia emissions.

“We are taking the starch

away from the feed, but what is the effect of this on the animal?” asks Van der

Aar. The level of starch in the diet has

an effect on stimulation of protein

deposition – the protein-fat ratio in the diet. Also, fertility is affected and

yolk-albumen ration in eggs might change

if starch levels decrease.

Additionally, feed and food safety will be challenged with the increased use of

DDGS, explained Van der Aar. A concentration of contaminants can occur,

specifically mycotoxins. Pigs are very susceptible to these toxins. Residues of

crop protection agents can also enter the feed chain through DDGS. Furthermore,

the US will try to export their surplus of DDGS; however, antibiotics used as

production aids in the US might hamper exports to Europe. The EU has a

zerotolerance for in-feed antibiotics. Another co-product of ethanol production

is glycerol. Although trials have shown that it can be used as a feed

ingredient, glycerol in feed is prohibited in the US due to possible methanol

residues from the production process. The use of these new ingredients can

affect husbandry aspects, and can also alter the quality of animal products.

Here, one can think of saturation of fat, water holding capacity, litter quality

and indirect effects on animal health.

Inclusion levels

In terms of costs, DDGS has different values depending on

the feeds it is

| |

used in. Table 4 shows

the value of wheat DDGS in different feeds. Nutritionally, research for maximum

levels of critical compounds (glucosinolates, unsaturated fatty acid, soluble

NSPs) is required. The levels of inclusion depend on levels of critical

compounds in other ingredients used. What will the input for least-cost

formulations be? There are more restrictions for the use of biofuel products.

The use of rape products is limited due to their ANF content (glucosinates,

saponins). There is little knowledge about the net energy value of glycerol, and

DDGS varies too much in terms of quality, protein digestibility and fermentable

NSPs. What about the high P and N excretion? Taken all these factors into

account, Van der Aar generated possible practical incorporation levels for

| |

wheat DDGS. These are illustrated

in Table 5. The availability of protein-rich ingredients and the

greater demand for starch for biofuels means that the feed industry is faced

with more expensive starch sources. This also results in less starch in the

diet. There will also be more pressure on glucose precursors in the diet.

Minimum starch requirements need to be re-evaluated regarding physiological

requirements, optimal production and energy requirements.

Source: Feed Tech magazine, Issue

11.8